1. The Quiet Variable

Productivity is the quiet variable in the national equation. It moves without spectacle, yet its motion determines nearly everything else: fiscal resilience, wage growth, competitiveness, and the confidence of institutions to promise a future. Unlike fiscal balances or inflation rates, productivity’s drift is not easily visible. It manifests in the slow divergence between effort and output; between the size of the system and its capacity to renew itself.

From 2000 to 2025, Canada’s productivity line has traced a restrained arc—rising modestly in the early 2000s, plateauing through the 2010s, and softening again as post-pandemic distortions met structural fatigue. Figure 1, The National System as Mosaic: Provincial Arcs of Capital and Competence (2000–2025), captures this fragmentation. Each provincial trajectory reflects a different composition of capital, workforce, and policy bias. British Columbia’s curve aligns with a service-driven economy tethered to real estate and port logistics; Alberta’s reflects capital intensity without diversification; Ontario’s blends high-value manufacturing with public administration; Quebec sustains stability through public investment and technological clusters. The Atlantic provinces and the North mark flatter arcs—leaner economies, yet more stable ratios of output per worker.

The mosaic is not only spatial but institutional. Productivity stems from how jurisdictions convert inputs into durable advantage. Capital deepening without innovation yields diminishing returns; innovation without diffusion creates islands of excellence surrounded by mediocrity. The figure shows how these contradictions accumulate. The provinces that invested in applied technology and workforce mobility maintained steadier growth in multi-factor productivity, while those relying on housing and resource cycles faced volatility masked as prosperity.

In structural terms, the mosaic resembles a balance sheet under the IMF’s Government Finance Statistics framework: assets distributed unevenly across regions, liabilities embedded in aging infrastructure and debt-weighted households. The result is a system that expands fiscally while contracting in productive depth. Figure 1’s variation is therefore diagnostic—a visual map of how Canada’s federation internalizes divergence while presenting the appearance of stability.

The quiet variable, then, is not productivity itself but the institutional attention paid to it. Policy debates orbit around redistribution and resilience, rarely around the machinery of output. Yet the graph reminds that the slope of productivity determines the ceiling of ambition. When it flattens, so too does the capacity to finance vision, to renew infrastructure, and to sustain the narrative of progress.

2. Capital without Compounding

Investment has not vanished; it has changed direction. Over the past fifteen years, fixed-asset formation in housing has outpaced business investment by more than two-to-one. Every dollar that builds a condominium tower in Vancouver or Toronto is a dollar not building export capacity, logistics corridors, or manufacturing renewal elsewhere. The result is a capital-deepening paradox: rising asset values, stagnant productive capacity.

Beneath that paradox sits a structural rhythm seen in every late-cycle economy. It begins with rational caution, evolves into cultural habit, and ends as institutional doctrine. The shift from productive to protective capital follows a predictable logic—what the system defends becomes what it depends on.

Safety Preference:

In the first phase, investors and households migrate toward assets perceived as safe. After the shocks of the early 2000s and the financial crisis of 2008, risk tolerance across Canada narrowed. Families sought stability through home ownership, and institutions mirrored that instinct through balance-sheet conservatism. Real estate, with its visible and collateral form, became the vessel for both savings and sentiment. The private sector’s capital allocation tilted away from innovation and export infrastructure toward tangible stores of value that promised certainty. Productivity, meanwhile, depends not on the amount of capital held, but on how fluidly it moves through systems that create value.

Policy Reinforcement:

Governments, seeking to preserve stability, reinforced the trend. Mortgage insurance frameworks expanded, tax incentives favored property accumulation, and fiscal programs emphasized consumption over industrial renewal. The IMF’s Government Finance Statistics framework would record this as a shift within the balance sheet: public liabilities supporting private asset inflation. Policy, intended to steady the system, effectively institutionalized the preference for static capital. Public guarantees reduced perceived risk, amplifying leverage and drawing more private credit toward non-productive assets.

Narrative Feedback:

Once entrenched, the cycle sustains itself through language and perception. Rising property values become proof of collective competence; balance-sheet gains are mistaken for productivity gains. Households equate appreciation with achievement, and policymakers read stability as success. The media narrative, shaped by recurring data on home prices rather than export indices, rewards continuity over transformation. In such an environment, risk-taking loses its moral license.

By the 2020s, housing and financial assets had absorbed the country’s surplus liquidity. The productive frontier—innovation, manufacturing, logistics—faced capital scarcity even as total investment soared. The charts that follow trace this divergence: the visible accumulation of wealth masking the invisible erosion of compounding. When a nation mistakes asset inflation for productivity growth, it ceases to build the engines of renewal and begins to monetize the illusion of it.

3. Labour, Technology, and the Diffusion Failure

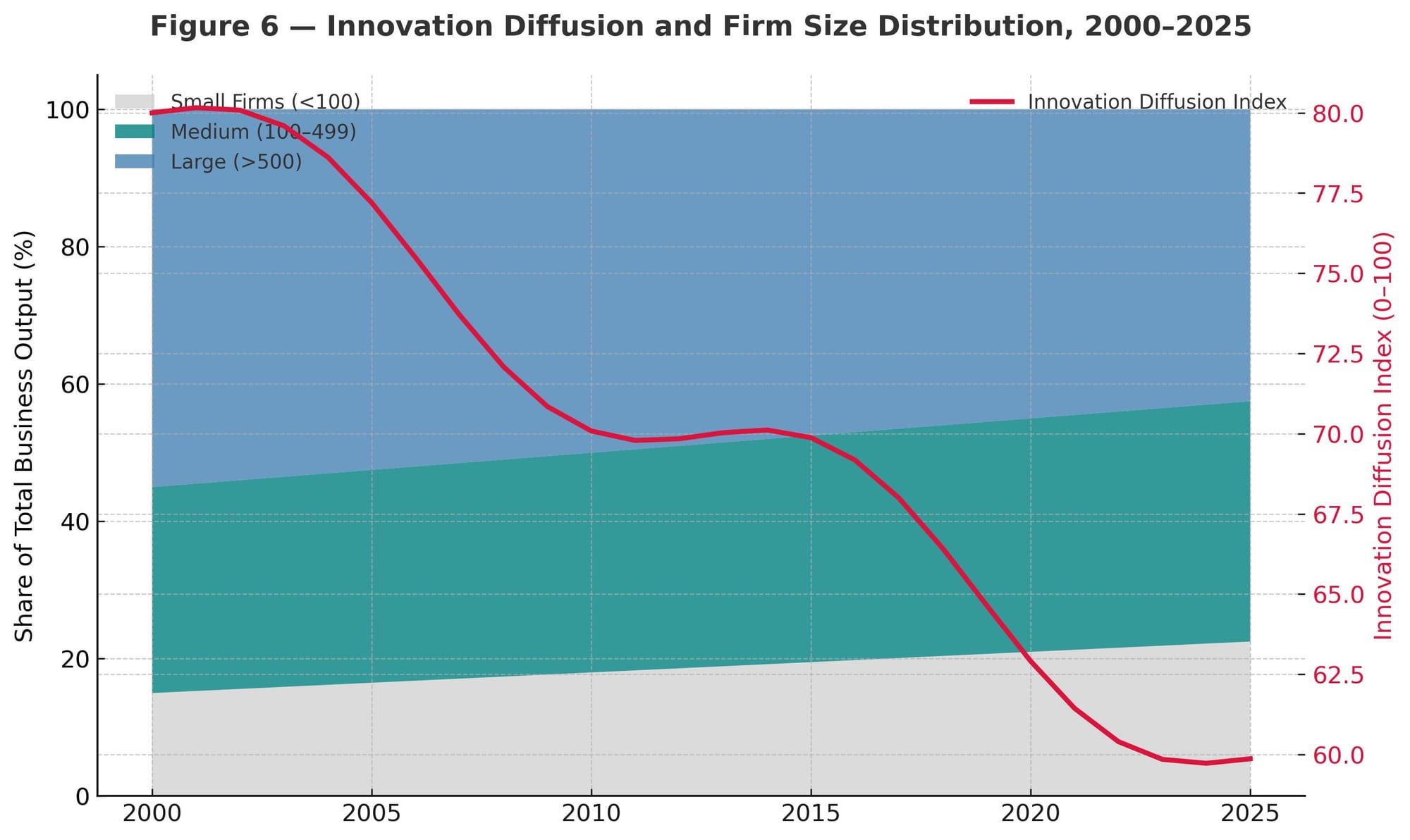

For much of the past twenty-five years, Canada’s productivity conversation has revolved around innovation. The assumption was that invention itself would close the gap. It has not. The deeper constraint lies not in creation but in diffusion, the economy’s capacity to transmit technology, skills, and capital from the frontier to the median firm. The tools exist, the talent exists, the capital exists; what fails is their circulation.

Figure 2, Innovation Diffusion and Firm Size Distribution (2000–2025), visualizes this asymmetry: a narrow cohort of frontier firms advancing rapidly, while the majority of small and mid-sized enterprises persist with limited efficiency gains. The figure’s curvature captures a central paradox of the Canadian system, an economy that innovates at the edges yet stagnates at the core.

The diffusion failure unfolds through three dominant friction points that compound over time, each reflecting a disconnect between technological capacity and institutional design.

Firm Size Distribution:

Ninety-eight percent of Canadian businesses employ fewer than one hundred people. Scale economies seldom form, and few reach the thresholds that sustain continuous R&D or export momentum. Larger firms integrate digital systems, data analytics, and automation with relative ease; smaller firms remain anchored to legacy tools and thin margins. In the visual data, this imbalance appears as a widening gap between the top decile of firms and the long tail of small enterprises. The result is a productivity gradient that mirrors the income gradient, steep at the frontier and flat across the median. Where the United States or Germany diffuse innovation through clustered supply chains and mid-tier scaling, Canada’s atomized structure dissipates gains before they compound.

Inter-provincial Trade Barriers:

The second friction is jurisdictional. Regulatory mismatches between provinces, including differing standards, certifications, and procurement rules, fragment the national market more than many international borders. The diffusion of technology depends on the scale of exchange and the consistency of rules that govern it. Fragmentation reduces both demand and learning spillovers. A startup that scales in Ontario must navigate new compliance systems in Alberta or Quebec; a manufacturer that upgrades its production methods in Manitoba must re-certify elsewhere. The barriers that appear administrative in form are economic in substance, suppressing the velocity of adoption. In macroeconomic terms, it functions like an internal current-account friction within a single sovereign balance sheet

4. Fiscal Design and the Incentive Drift

Over the past two decades, Canada has relied on fiscal design to manufacture competitiveness. Each new government, regardless of ideology, has turned to targeted credits, subsidies, and incentives to encourage productivity. The intention is sound; the effect, limited. Tax-based innovation support now exceeds ten billion dollars each year, yet national research and development intensity has barely moved.

The issue is not generosity but structure. Incentives accumulate within vertical silos rather than spreading across the broader economy. Figure 3, Fiscal Incentives and Innovation Concentration (2000–2025), shows how tax credits and grants have clustered around a few favored sectors such as clean technology, digital media, and advanced manufacturing. These programs create momentum within selected domains but leave most of the productivity base untouched. The result is a concentration of policy effort without diffusion of impact.

Each incentive program builds its own administrative machinery and evaluation system. Layers of reporting and eligibility rules multiply across departments, turning what should be a catalyst into a maze. Firms learn to navigate policy rather than markets, aligning business models with grant criteria instead of long-term competitiveness. Innovation becomes procedural rather than productive.

In the short run, these incentives create the appearance of activity. Press releases, pilot projects, and new funding envelopes suggest movement. Yet the aggregate data reveal little change in total factor productivity or private investment per worker. The system rewards access over output and continuity over experimentation. Over time, fiscal design begins to institutionalize dependency. Innovation becomes defined by application cycles, and productivity becomes something pursued through compliance rather than competition.

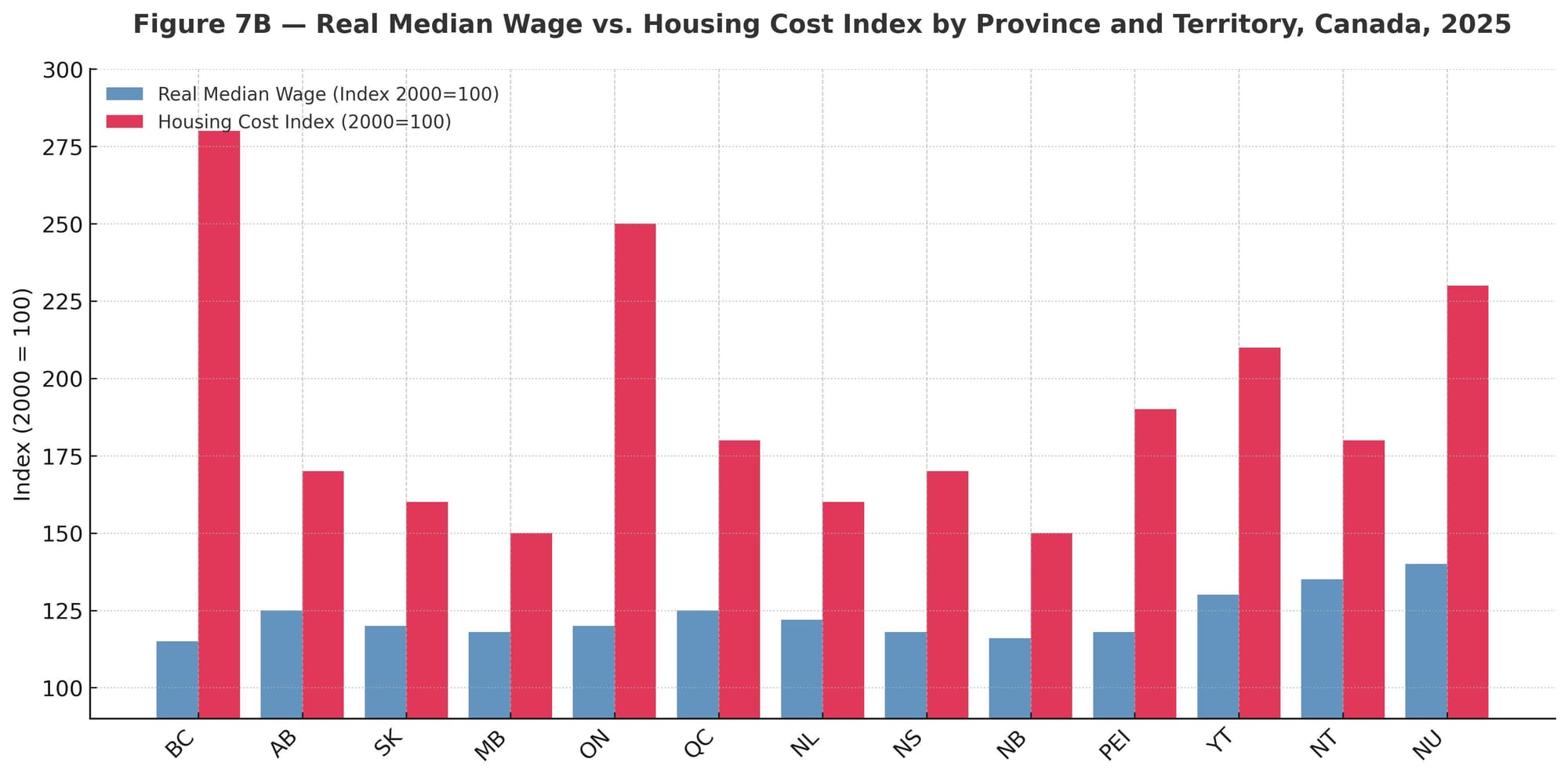

5. Household Economics and the Wage Illusion

For most Canadians, productivity is not an abstract statistic but a lived experience measured through wages, prices, and the cost of daily life. Over the past two decades, real median wages have barely risen even as GDP per capita increased. The difference has been absorbed by housing costs, transportation, and debt service. Figure 4, Real Median Wage vs. Housing Cost Index (2000–2025), makes this visible: household income lines moving sideways while the cost-of-living curve climbs steadily upward.

This divergence has altered not only household finances but also the national mood. A generation raised to believe that education and effort would secure advancement now measures success by stability. Upward mobility has become endurance; optimism has been replaced by caution. Confidence remains part of the culture, yet ambition narrows as people redirect energy from long-term investment to short-term consumption. What once signaled growth now signals strain.

The psychological effect mirrors the fiscal one. Rising asset values give the illusion of prosperity, but they do not expand real opportunity. Families own more on paper while feeling poorer in practice. Wages stagnate while fixed costs rise, and the promise that productivity growth will translate into living standards fades from experience.

This erosion of the wage-productivity link is more than an economic concern; it is a civic one. When work no longer delivers progress, the credibility of institutions that claim to reward merit begins to weaken. The social contract, once grounded in the expectation that effort yields improvement, is replaced by a quieter transaction: citizens maintain faith in the system, and the system maintains the illusion of fairness.

6. Regional Patterns of Divergence

Productivity across Canada follows distinct regional geometries. Figure 5, Provincial Productivity Divergence (2000–2025), traces these patterns in both scale and volatility. The federation’s aggregate numbers appear stable, yet beneath them lies a landscape of uneven capacity and contrasting economic rhythm.

Alberta and Saskatchewan lead in GDP per worker but remain tethered to global commodity demand. Their productivity peaks coincide with resource booms and fall sharply during downturns. Capital intensity drives short-term surges, yet diversification remains limited. The West’s strength is scale; its weakness is dependence.

Ontario and Québec anchor the national labour force and absorb most of the country’s industrial and service employment. Productivity gains here are moderated by congestion, high operating costs, and an aging urban infrastructure. Ontario’s advanced manufacturing and financial sectors sustain competitiveness, while Québec’s public investment and innovation clusters offset slower private capital formation. Both provinces balance size with friction.

The Atlantic provinces trade stability for stagnation. Their economies rely heavily on public administration, health care, and education, supported by federal transfers that cushion volatility but suppress dynamism. Productivity growth has been modest, shaped more by demographic trends and fiscal support than by structural renewal.

The territories oscillate between boom and subsistence. Large extractive projects generate temporary spikes in GDP per worker, followed by long stretches of low activity. Sparse infrastructure and high costs constrain both investment and labour mobility. Productivity in the North mirrors geography itself: vast potential, intermittent realization.

Together, these asymmetries define Canada’s national equilibrium—resilient in aggregate, restless in detail. The country’s stability depends on a rotating balance: when one region slows, another rises. Yet this equilibrium conceals the deeper challenge of convergence. Without stronger internal diffusion of capital, technology, and trade, the federation risks mistaking rotation for renewal.

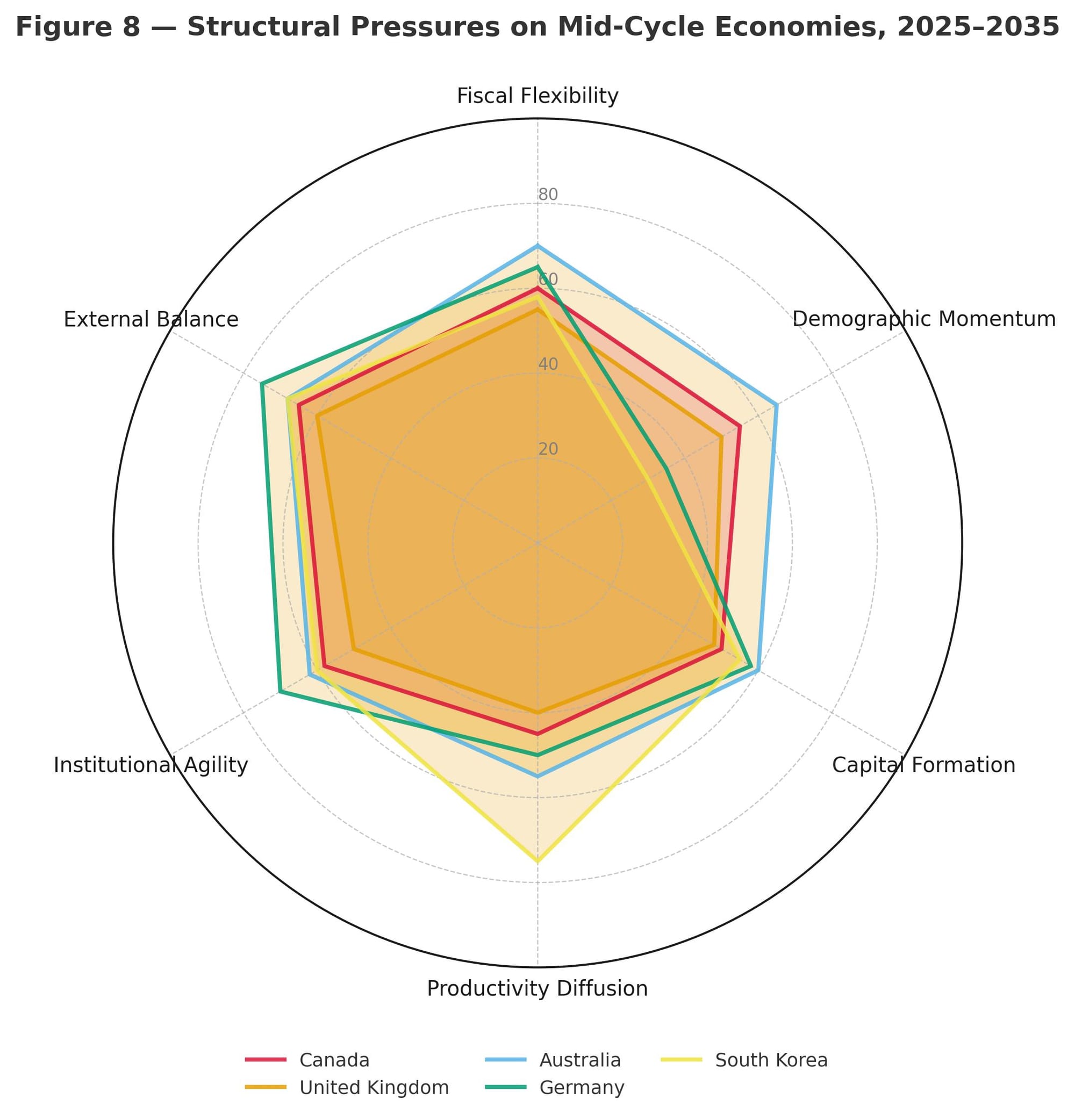

7. Global Context — The Era of Costly Capital

Canada’s productivity story now unfolds within a harder global setting. Figure 6, Structural Pressures on Mid-Cycle Economies (2025–2035), situates the national slowdown within the broader shift from cheap capital to costly capital. The long era of low interest rates, abundant liquidity, and seamless trade has given way to tighter money, fragmented supply chains, and renewed geopolitical risk. For a mid-sized, trade-dependent nation, these shifts amplify structural limits that had previously been masked by global tailwinds.

Public and private debt alike are maturing into a higher-rate environment. The fiscal cushions that once absorbed shocks are thinner, and refinancing costs climb even for stable borrowers. For households, this means a prolonged squeeze between mortgage payments and stagnant wages. For firms, it means investment decisions governed by cash flow rather than credit. In aggregate, the cost of capital is no longer a policy variable; it is a structural constraint.

Resource exports, long the anchor of western productivity, now face reduction in carbon emission mandates and shifting demand patterns. Oil and gas remain valuable but increasingly capital-intensive and politically exposed. At the same time, global demand for critical minerals—lithium, nickel, copper—creates new opportunities that depend on infrastructure and regulatory agility Canada has yet to deliver. The transition is not a clean swap but a race between declining assets and emerging capabilities.

Population growth sustained by immigration maintains labour supply but strains urban systems. Housing, transit, and healthcare lag behind demographic momentum, reducing the net gain from workforce expansion. The challenge is no longer quantity but quality, how to align new workers with the skills, tools, and industries that raise output per hour rather than merely increase hours worked.

Together, these forces compress the margin for easy growth. Where earlier decades allowed productivity to be deferred through borrowing, resource rents, or globalization, the new environment does not. The next cycle demands internal efficiency, institutional coordination, and genuine innovation rather than narrative optimism. Canada’s future competitiveness will depend on how quickly it can convert stability from a comfort into a capability.

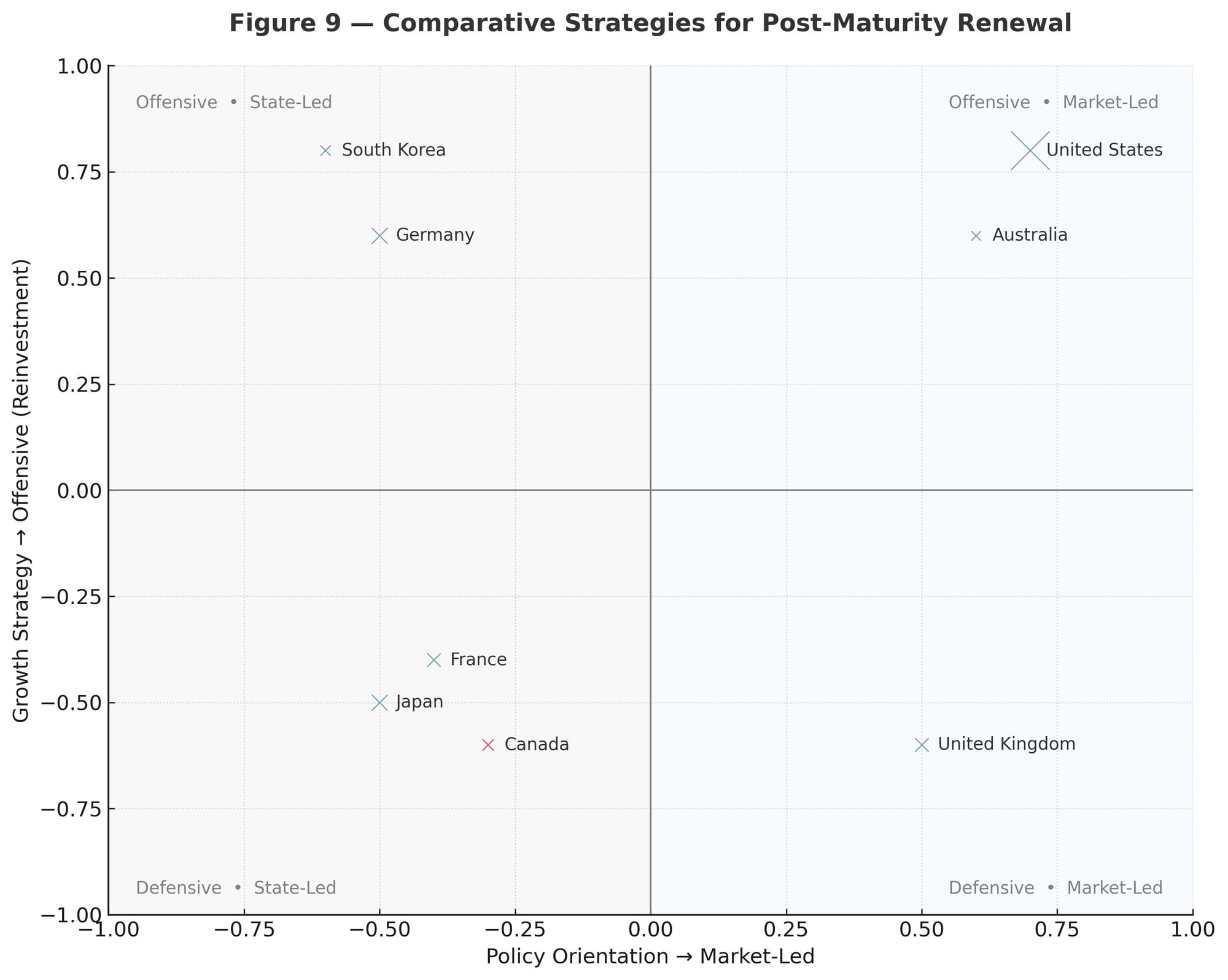

The productivity challenge is not only economic but institutional. Figure 7, Comparative Strategies for Post-Maturity Renewal, maps the interaction between Canada’s structural forces and the behaviors of its governing systems. The data and policy record reveal a country optimized for stability rather than acceleration. The machinery functions, yet it does not evolve.

Capital deployment in Canada moves slowly. Permitting processes stretch across multiple jurisdictions, each with overlapping authority and procedural caution. Infrastructure projects, energy developments, and industrial expansions often take years to clear even preliminary review. The result is not deliberate oversight but friction—time and cost accumulating in the spaces between governments. When institutional coordination becomes the limiting factor of productivity, efficiency cannot be legislated; it must be governed.

The backlog in both transport and digital networks continues to inflate costs and constrain regional parity. Congested ports, delayed rail expansions, and uneven broadband access fragment the national market. Productivity gains in core provinces rarely transmit to peripheral ones because the connective tissue of the economy remains under built. The deficit is not merely fiscal but strategic: under investment in enabling infrastructure prevents the diffusion of technology and the scaling of enterprise.

Tax and regulatory systems continue to reward property accumulation and consumption over production. Housing, treated as a financial asset, captures both household savings and investor capital that might otherwise fund business investment or innovation. Policy frameworks designed to stabilize markets inadvertently distort them, reinforcing the imbalance between asset inflation and productive growth.

A preference for stability shapes both politics and business. Risk-taking remains the exception rather than the norm. Institutions prize predictability, firms avoid volatility, and citizens expect security as a policy outcome. This equilibrium, once a source of resilience, now limits adaptation. When a society defines success as the absence of disruption, it gradually loses the capacity for transformation.

Taken together, these four constraints explain the paradox visible throughout the preceding figures. The economy remains functional, employment steady, and living standards high by global measure, yet momentum erodes beneath the surface. Canada’s institutions preserve order, but order alone cannot generate growth.

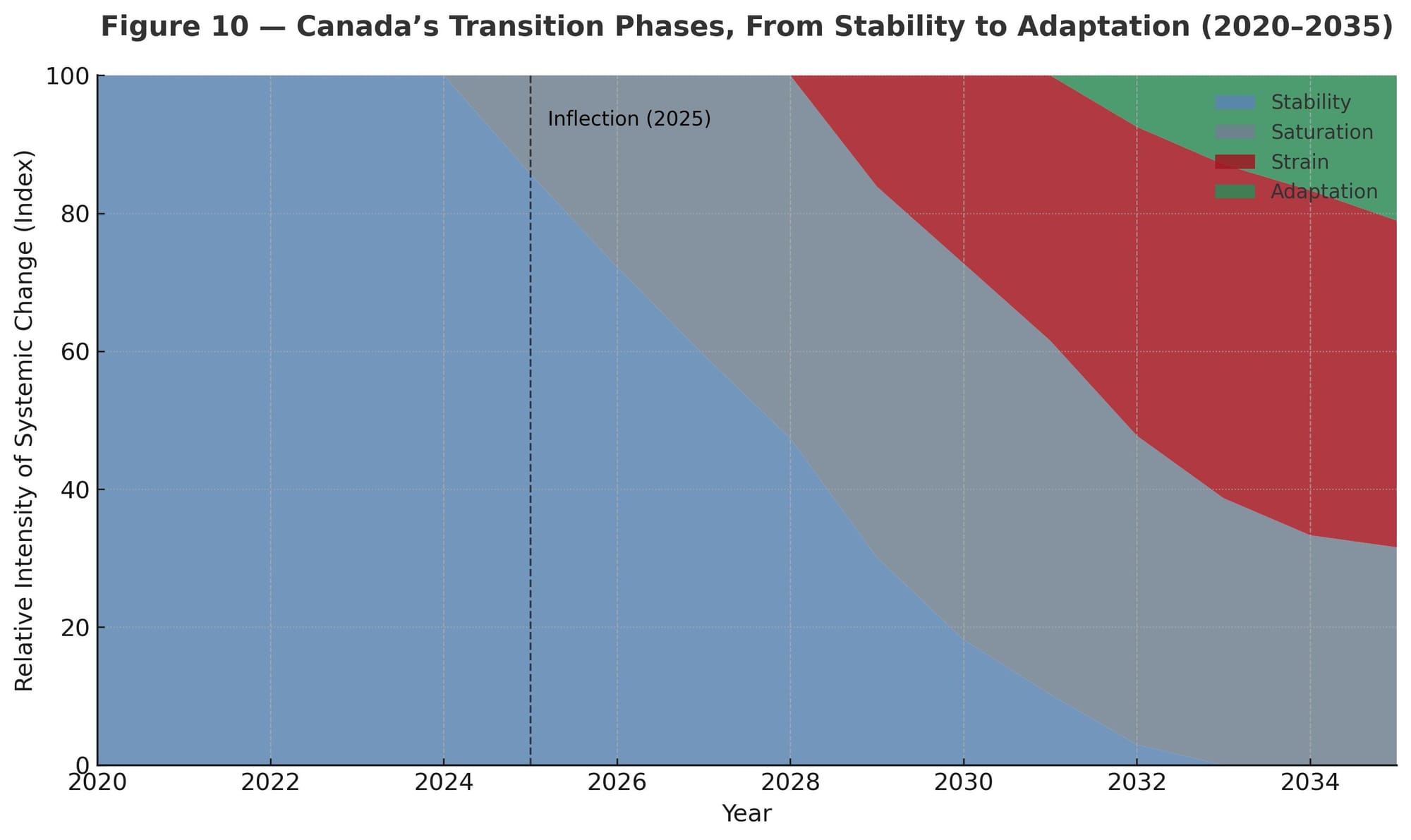

Reversing structural decline will not hinge on a single reform but on a coordinated sequence of actions. The challenge is systemic, and so must be the response. Figure 8, Transition Phases: From Stability to Adaptation, outlines the progression required to move from preservation to renewal. The shift involves fiscal realism, institutional simplification, and a cultural permission to fail—conditions that allow the economy to adapt rather than merely endure.

Simplifying inter-provincial trade and procurement rules is the most immediate lever. By reducing duplication and harmonizing standards, small and mid-sized firms can grow beyond local markets and participate in national supply chains. Scale transforms productivity from an abstract target into a structural property of the system. When firms can operate seamlessly across provinces, innovation spreads faster and investment returns multiply.

Infrastructure should no longer be seen as a final output but as a foundation for private enterprise. Projects in transport, energy, and digital connectivity must be designed to crowd in investment, not replace it. Public capital that enables private ecosystems generates compounding effects across sectors, creating a shared base for diffusion rather than a temporary fiscal stimulus.

Labour policy must pivot from credential expansion to skill application. Training systems should prioritize applied technical fields that align with automation, energy transition, and advanced manufacturing. Immigration frameworks must focus on skill diffusion rather than headline population growth. A workforce that can adapt technology across sectors is the single most direct route to sustained productivity gains.

A credible revival begins with measurement. Publishing standardized productivity dashboards by sector and region would allow policymakers, investors, and citizens to evaluate outcomes in real time. Clear data demystifies productivity, transforming it from a technocratic concern into a national accountability metric.

Each reform, on its own, may appear incremental, but together they redefine the incentive structure of the Canadian economy. Revival depends less on new policy instruments than on the courage to streamline the ones already in place. Productivity, once restored to the center of national purpose, becomes not only an economic imperative but a civic renewal.

10. The Narrative Dimension

No productivity strategy can endure without a story that binds effort to purpose. Figure 9, National Narratives and Structural Renewal (1960–2025), traces how each growth era in Canada was driven by a prevailing idea: industrialization in the 1960s, globalization in the 1990s, and innovation in the 2010s. Each narrative mobilized confidence, delivered real progress, and then settled into complacency once its promise became routine. The next phase will depend on whether the country can construct a narrative of renewal that acknowledges constraint while preserving ambition.

Canada’s institutions have long excelled at maintaining order but have struggled to translate that stability into forward momentum. A new narrative must move beyond the language of optimism and into the practice of competence. It must accept that limits are not failures but coordinates within which renewal is possible. The realism required is not pessimism but proportion—an understanding that prosperity will depend less on global cycles and more on internal discipline.

A society that measures success only through consumption cannot innovate, and a political culture that equates reform with austerity cannot adapt. The public discourse must reconnect productivity with lived experience, showing that efficiency is not abstraction but the means by which wages rise, services improve, and independence is preserved.

The task for institutions is therefore rhetorical as much as economic. They must rebuild belief in competence not as spectacle but as service. Confidence grounded in performance rather than promise is what sustains long-cycle renewal. The narrative of productivity must evolve from slogans to stewardship, from ambition declared to ambition delivered.

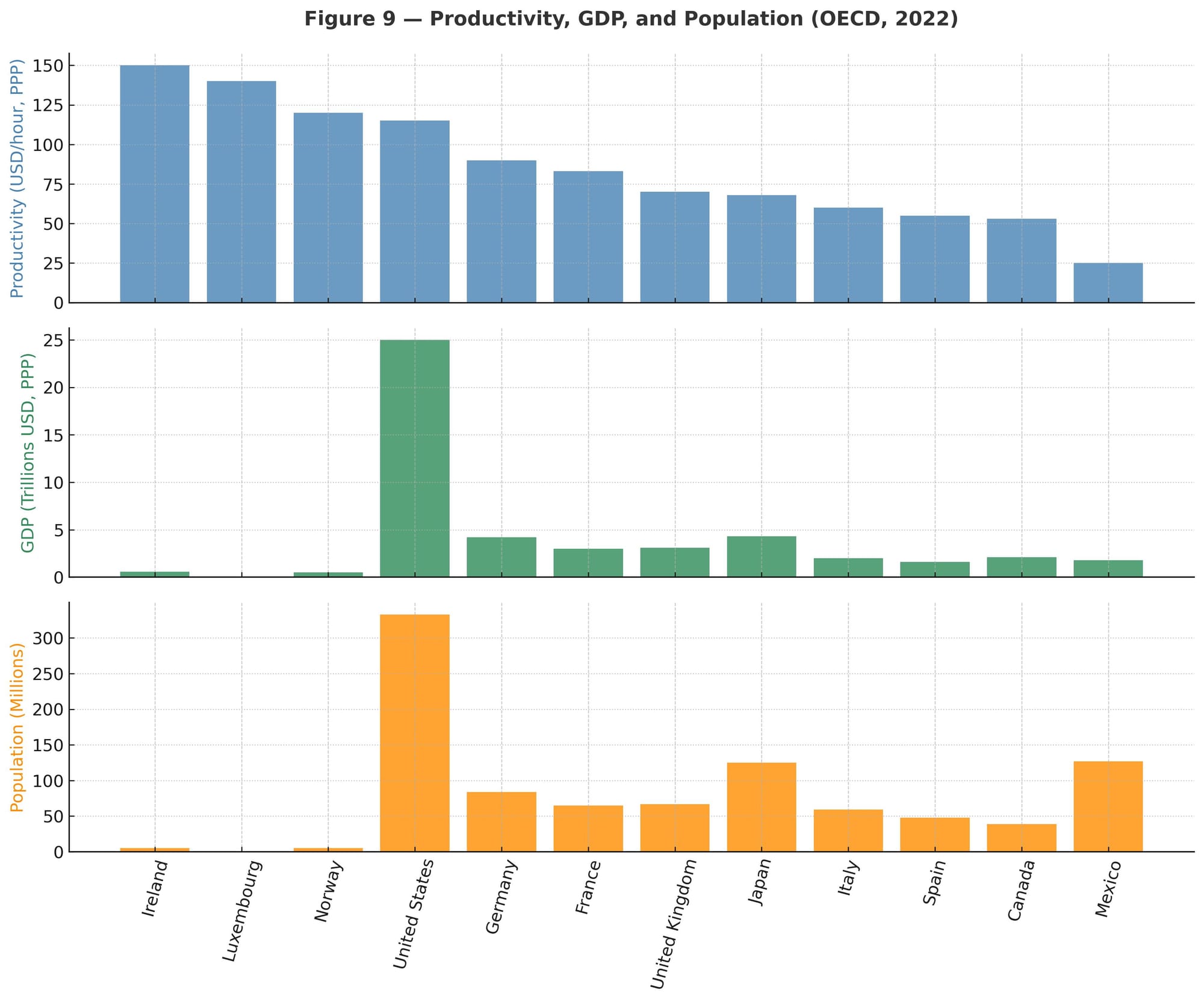

11. Comparative View — Learning from Peers

Several peer economies have demonstrated partial escape routes from stagnation. Their experiences show that structural renewal depends less on ideology than on institutional clarity and disciplined reinvestment. Figure 11, Comparative Frameworks for Post-Maturity Economies, contrasts Canada’s trajectory with three illustrative models—Australia, Norway, and the Netherlands—each achieving renewal through a distinct strategic focus.

Australia:

Australia leveraged its resource wealth to fund long-term stability. By converting commodity rents into sovereign reserves and investing heavily in higher education, research, and immigration-linked human capital, it created a second growth engine beyond mining. The transition from extraction to knowledge exports anchored the country’s competitiveness. Its lesson for Canada is not scale but sequencing: converting windfalls into durable capacity before the cycle turns.

Norway:

Norway institutionalized its energy surplus through transparent fiscal architecture. The Government Pension Fund Global, designed to operate beyond partisan influence, turned volatile oil revenue into inter-generational wealth. This model shows how disciplined governance can transform resource dependence into financial sovereignty. Canada’s energy sector shares similar potential but remains embedded within political and regional negotiation rather than unified strategy.

Netherlands:

The Netherlands re-positioned itself through logistics and digital infrastructure. Its ports, energy networks, and data centers form a tightly integrated platform that amplifies scale despite limited geography. By focusing on coordination and efficiency, the Netherlands turned a small domestic base into a continental hub. For Canada, the parallel lies in infrastructure as leverage—using connectivity, both physical and digital, to multiply productivity across regions.

Singapore – Strategic Compactness

Singapore overcame geographic and resource constraints through precision governance and infrastructure-led statecraft. Long-term industrial planning linked education, housing, and logistics under one strategy. Productivity gains were driven by predictability—policy consistency across decades. For Canada, the takeaway lies in institutional coordination: aligning fiscal, educational, and urban policies into a single productivity mandate rather than treating them as isolated files.

Finland – Human Capital and Resilience

Finland turned a post-industrial collapse in the 1990s into a model for education-driven innovation. By coupling universal technical literacy with targeted R&D partnerships, it transformed small-scale industries into export leaders. The lesson is that productivity begins in classrooms and diffuses through trust between government and enterprise. Canada’s skills strategy could learn from Finland’s alignment of curriculum with industrial policy, ensuring that applied learning becomes a core pillar of renewal.

South Korea – Sequenced Industrialization

South Korea illustrates how strategic state intervention can scale private capacity. Through phased industrial policy, export orientation, and disciplined credit allocation, it built competitive advantage in manufacturing and technology without losing fiscal control. Its model underscores the value of sequencing—supporting sectors only until they achieve market self-sufficiency. For Canada, this approach could guide a transition from subsidy dependence toward measurable performance thresholds in innovation funding.

Germany – Mittelstand Strength

Germany’s productivity stability rests on its mid-sized firms, the Mittelstand, which balance scale and adaptability. These firms sustain high R&D investment and vocational training through tight integration with regional institutions. Canada’s small-business landscape mirrors Germany’s in structure but not in coordination. The German example demonstrates how federated systems can thrive when national and regional policies reinforce shared industrial foundations.

Denmark – Green Competitiveness

Denmark turned environmental constraint into comparative advantage. Its early investment in wind energy, sustainable manufacturing, and design-based innovation positioned it as a leader in green exports. The country’s regulatory clarity and collaboration between public and private sectors fostered long-term confidence in transition industries. Canada’s energy transition, still fragmented by jurisdiction, could draw from Denmark’s emphasis on predictable frameworks and early public consensus.

Each model demonstrates a different method of renewal: Australia through reinvestment, Norway through insulation, and the Netherlands through integration. Canada shares traits with all three yet replicates none. Its task is to adapt these lessons into a uniquely federal framework that binds regional autonomy to national coherence. Renewal will require translating capacity into cohesion, ensuring that the federation’s diversity becomes an engine of adaptability rather than a constraint on it.

12. From Decline to Adaptation

Structural decline is not collapse; it is the moment when a nation recognizes that its growth model has completed its cycle. Figure 12, Transition Phases: From Stability to Adaptation, captures this passage for Canada, showing a country that remains prosperous yet increasingly defined by inertia. The model that carried the last generation—immigration-driven expansion, resource rents, and housing liquidity—delivered stability at the expense of momentum. What once generated resilience now sustains dependence.

Decline begins not with loss but with repetition. The same levers that once fueled growth now reproduce diminishing returns. Resource rents buffer downturns but discourage diversification. Immigration supports demand but strains infrastructure. Housing creates paper wealth while diverting capital from production. The structure endures, but its energy fades. This is the essence of late-cycle maturity: a system that continues to function while gradually losing its capacity to adapt.

The path forward lies in converting stability into movement. Canada must redirect confidence from consumption to creation, from passive accumulation to active renewal. This requires more than policy adjustment; it demands a cultural decision about what the country values. Productivity revival will depend on whether success is measured by the price of assets or by the capability to build, design, and produce.

Adaptation will mean using fiscal discipline as a foundation for experimentation, not as an argument against it. It will mean modernizing institutions so that efficiency becomes the natural outcome of coordination rather than the exception achieved through reform. It will mean rebuilding public belief that competence and creativity, not mere growth, define national strength.

The next cycle will not resemble the last. The world of cheap credit and friction-less trade is receding, replaced by one that rewards resilience and internal capability. For Canada, this is not decline but invitation, a call to move from preservation to purpose. The choice is clear: remain a nation that measures progress in prices, or become one that measures it in what it can build, sustain, and renew.

Transition to Section III

Productivity defines the nation’s internal mechanics, yet the Canadian story is also geographic: a federation of economies moving through different stages of the same structural cycle.

The following section examines those provincial and territorial arcs in detail: how each region converts capital into competence, and why the sum of their differences constitutes the modern Canadian system.